26-09-23

Yellow laugh – a conversation with Ghita Skali

For Ghita Skali, being an artist is a job like any other. A job that, as she explains, is sometimes motivated by desire. But it is a job. One in an exploitative capitalist environment, no less.

Auteur Lena van Tijen

Meet Joep de Jong, a white, middle-aged Dutchman proud of his country. To give an impression: Joep is tremendously fond of tulips. He works as a tour guide in Amsterdam. And, every morning, he wakes up with the song 15 miljoen mensen by Fluitsma & Van Tijn playing in his head. But there is a problem: Joep cannot find a watering can for his beloved flowers anywhere. Each time he goes out to buy one, a person of color beats him to the chase. As it turns out, they use watering cans to water something other than plants. So, the Dutchman despairs. He eats his tulips and ends up hallucinating. This story sounds like a joke. But it is the plot of Natuurlijk, the latest video by Moroccan artist Ghita Skali. But for the sake of argument, let us call it a joke. Because if it were, Joep would be the butt of it.

By telling the story of Joep, Skali reflects on Western hygiene habits and their surrounding bias. Why is washing your butt with water considered strange in the Netherlands when in many other countries it is part of the natural order of things? Why do the 15 million Dutch people from the song by Fluitsma & Van Tijn – now 17 million – look down upon this habit while outnumbered?

These are the questions she poses in Natuurlijk, which was on show at 1646 in The Hague till the 9th of July 2023. Skali does not ask these questions outright but hints at them through a narrative technique she calls reversion. Instead of explaining why something is wrong – which the artist is tired of doing – she reverses stereotypical situations.

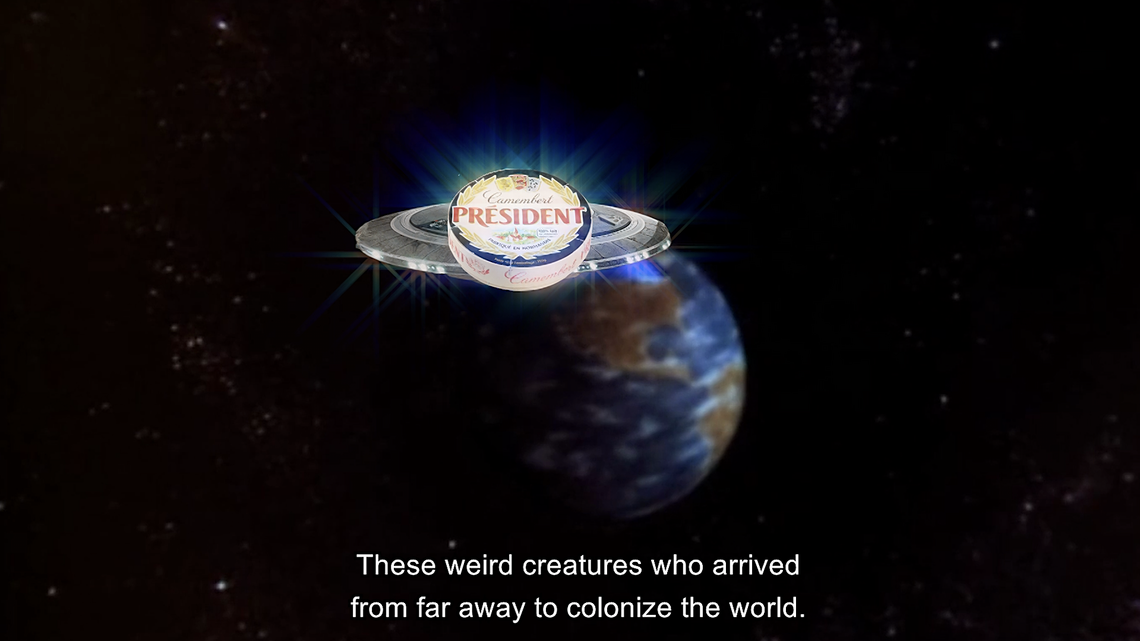

Natuurlijk is not the first instance in which Skali uses reversion. She also utilized the technique in The Invaders (2021). The video – which is in the collection of LI-MA – is a remake of Les Envahisseurs (1991), a sketch by the French humoristic trio Les Inconnus, which is itself a remake of The Invaders – a well know American tv-show from the 1960s.

The idea for the video arose during the first lockdown of the pandemic when the artist read (fake) news stories about Western tourists stuck – or not wanting to leave – the global South. The people that did not want to leave perceived the South as more hospitable and sometimes safer than their home countries.

A message that especially struck the artist was a meme published on Instagram, in which the world map is upside down. Taking her inspiration from the meme, Skali uses her remake of a remake to illustrate a role reversal. To show how migrants from the West are invading the South. To point at a flipped power dynamic.

Another narrative technique the artist uses is what she calls perverting hegemonic forms of art.

This technique is best explained by looking at The Hole's Journey (2020), which is also in the collection of LI-MA.

While in residence at De Ateliers in Amsterdam, Skali took a good look at the floor in the office of its former director Dominic van den Boogerd. The chair of Van den Boogerd – who was director of the institute for 23 years – had left deep traces in the parquet. Skali decided to remove the damaged floorboards and ship them to Morocco.

By removing the wood, the artist aimed at personifying two positions of power: that of the director sitting in the same place for so long that even the floor beneath him has grown tired. And of that which she calls rotten old Europe.

As a Moroccan artist, Skali gets confronted with the expectation to produce a discourse about her home country. To reflect upon her heritage. Instead of adhering to this expectation, she decided to reverse its logic. To create a Dutch artifact and send it to Morocco. She made this gesture when the debate surrounding the restitution of stolen African artifacts was heating up in Europe.

But what makes this project a perversion of hegemonic art forms and not – like Natuurlijk and The Invaders – reversion? Mainly, this distinction lies in the institutional critique the work offers. Next to exposing power structures, The Hole's Journey also absorbs these structures and enters into a playful dialogue with them. It does this by referencing artists Jan Dibbets and Ger van Elk – both strongholds in the Dutch conceptual art scene connected to De Ateliers. By pointing out the heritage of these artists, Skali acknowledges the local art history. But by – at the same time – approaching their legacy from a new perspective, she also questions its (mostly) undisputed presence in the art world.

Skali and I discuss these works while sitting at a café overlooking the Prinsengracht in Amsterdam.

The artist tells me she likes to put her finger where it hurts. At the same time, she is also critical of her role because art institutions are prone to absorb the critique they receive by, for instance, acquiring the very work they are questioned by.

Skali wonders how artists can keep making reproving art while knowing their criticality will eventually be soaked up by an institutional sponge.

In recent months, the complexity of this situation has only grown bigger for her. Skali is on the shortlist for the prestigious Prix de Rome. As we sit at the channel in Amsterdam, the artist is not at liberty to discuss any details surrounding her nomination. Still, she offers me her opinion on art prizes in general, which she finds reinforces toxicity, competitiveness, and the principle of meritocracy in the art world, plus keeping the myth of the artist genius alive.

For her, being an artist is a job like any other. A job that, as she explains, is sometimes motivated by desire. But it is a job. One in an exploitative capitalist environment, no less.

Discover more about Ghita Skali on her own website

Even if Skali finds that art prizes – and the art world – are often sexist, classist, and racist, she is not above winning one. She raises questions about the status quo.

But, she makes herself no illusion about escaping it. She does her best to claim her rightful place in the arts without being tokenized or marginalized.

And she does this using humor. For Skali, humor and satire are the driving forces behind her work. They are empowering devices, even political tools. According to the artist, humor helps to circumvent a victimhood narrative. And satire helps make critique more digestible. On an individual level, comedy makes Skali able to enjoy her practice. Even if she thinks being an artist is just a job, she is an artist because she is excruciatingly angry. And in dire need of a laugh.

Skali is not screaming in anger. But this does not mean she is not mad. It only shows that the artist did not choose to breach topics of injustice with a violent force. But with laughter. In her work, Skali uncovers the tension between anger and laughter.

She explains this by referring to a French expression: rire jaune, freely translated as the yellow laugh, which occurs when a person laughs even though they are angry, disappointed, uncomfortable, or sad. Laughing, even though one did not mean to laugh. The yellow laugh, Skali tells me, creates a moment of complicity as in her most recent work Natuurlijk. In the video, the people washing their butts with watering cans are one step ahead of Joep de Jong. An awkward realization that makes them chuckle. They are the ones in the know. And in this knowledge lies power.

Before Skali and I met, I read a review of The Hole's Journey in which the critic called the work: stronger and stranger than fiction. Though this is an apt description, after speaking to the artist, there is something I would like to add. In her practice, Ghita Skali also points to the absurdity of facts. While we sat at the cafe in Amsterdam, I asked her about the relationship between fact and fiction in her art. To which she replied: there is no fiction. Only facts. On the face of it, this statement might sound strange. But in all fairness, if one takes the time to examine what her work is actually about, when one looks beyond the humor and the satire, the ensuing realization might make you yellow laugh.